In the world of bodybuilding, where every rep counts and every set pushes you closer to your dream physique, exertion is the driving force behind your gains. Exertion, defined as the physical or perceived use of energy, is the effort you pour into each workout, whether it’s lifting heavy weights, performing high-rep sets, or pushing through fatigue. This article explores what exertion means in the context of bodybuilding, its physical and physiological dimensions, how to optimize it for muscle growth, and the risks of overdoing it. Drawing from scientific insights and practical experiences, we aim to provide a thorough guide for fitness enthusiasts and bodybuilders.

Defining Exertion in Bodybuilding

Exertion is the strenuous effort that results in the generation of force, initiation of motion, or performance of work, often related to muscular activity. In bodybuilding, it’s the energy expended during resistance training, such as lifting weights, which involves exerting force against gravity or resistance. This effort can be quantified through measurable metabolic responses, like increased heart rate and oxygen consumption, and is also perceived subjectively by how hard the workout feels.

From a physics perspective, exertion is the expenditure of energy against inertia, as described by Isaac Newton’s third law of motion: for every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction. When you lift a weight, you exert a force upwards, creating positive work done on the object, which stimulates your muscles to adapt and grow stronger over time.

Physical Exertion in Bodybuilding

Physical exertion in bodybuilding involves the use of force to perform work, such as lifting a barbell or pushing through a set of dumbbell presses. The work done is calculated as the force multiplied by the distance the weight is moved, a concept rooted in mechanics. For example, during a squat, you exert force through your legs and core to move the barbell, targeting those muscle groups for growth.

Newton’s third law is particularly relevant here: as you exert force on the weight, the weight exerts an equal force back on your muscles, creating the resistance needed for muscle stimulation. This physical effort is crucial for progressive overload, the principle of gradually increasing the weight, reps, or sets to challenge muscles and promote hypertrophy.

Muscular exertion generated depends on muscle length and the velocity at which it can contract, as noted in scientific literature. This means that the speed and range of motion during exercises like bench presses or pull-ups can influence how much effort is required and how effectively muscles are stimulated.

Physiological Responses to Exertion

When you engage in intense physical activity, your body undergoes a series of physiological changes to meet the increased energy demands, which are critical for bodybuilding:

- Increased Heart Rate and Blood Flow: Your heart beats faster to pump more blood to your working muscles, delivering oxygen and nutrients. This cardiovascular stress is a mediator of exertion, ensuring muscles have the energy to contract.

- Oxygen Consumption: Muscles consume more oxygen for energy production through aerobic respiration. During high-intensity exertion, when oxygen supply can’t keep up, muscles switch to anaerobic respiration, producing lactate. This shift is common during heavy lifting, where short, intense sets rely on anaerobic glycolysis.

- Lactate Production: The buildup of lactate leads to the burning sensation felt during intense sets, signaling high exertion. This is a normal response and can indicate that muscles are being pushed hard enough to stimulate growth, but it also suggests the need for rest to clear metabolic by-products.

These responses are essential because they prompt the body to adapt, enhancing its efficiency and leading to increased strength and endurance over time. Research from Lumen Learning highlights that anaerobic exercise, involving high-intensity bouts of exertion, utilizes primarily Type II muscle fibers, which are crucial for bodybuilding.

Perceived Exertion and Its Role

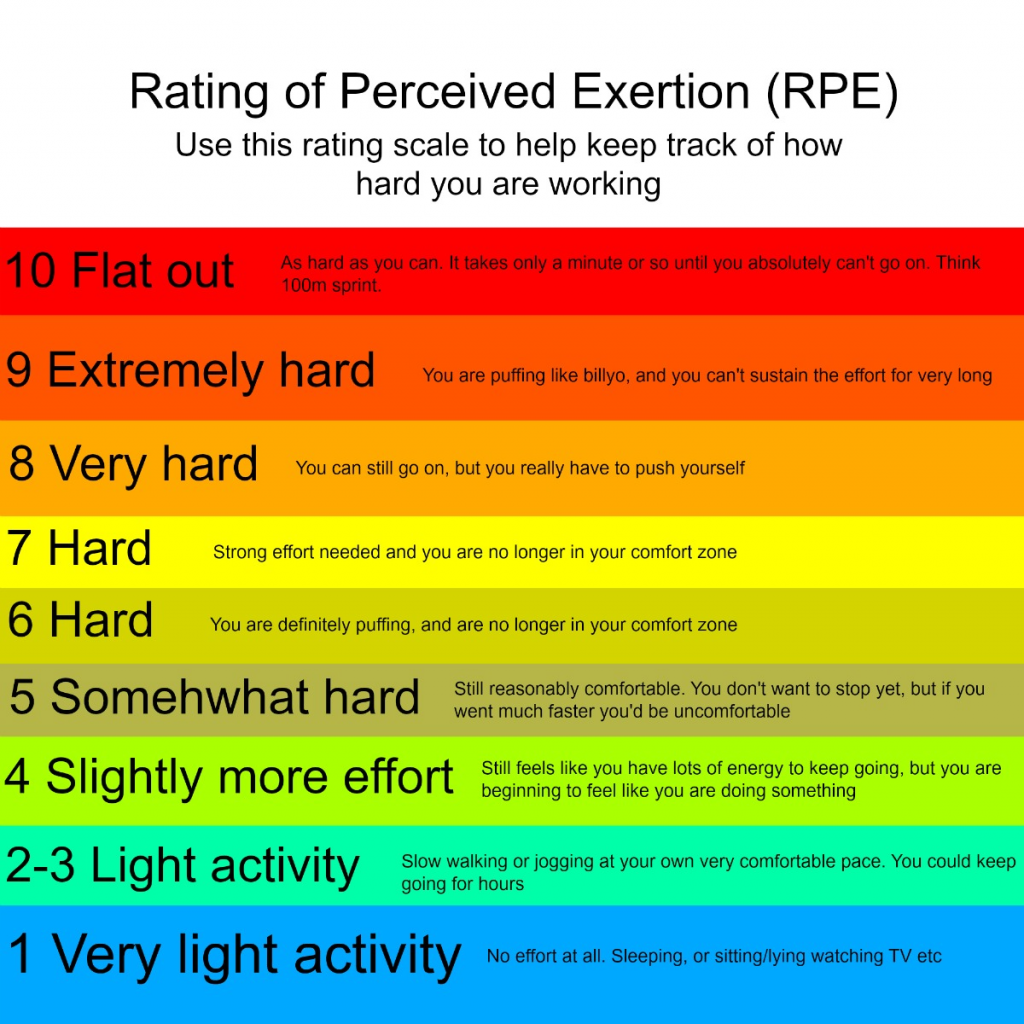

Perceived exertion is your subjective experience of how hard you’re working during exercise, influenced by factors like muscle fatigue, breathing rate, and overall discomfort. It’s a critical aspect of bodybuilding, as it helps you gauge whether you’re training at the right intensity for your goals.

The Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale, ranging from 1 (very light) to 10 (maximal effort), is a quantitative measure used to assess this. In bodybuilding, RPE is often used to monitor workout intensity. For example, an RPE of 7-8 is commonly targeted for hypertrophy training, meaning the last rep is challenging but manageable, aligning with the principle of pushing hard without reaching failure every set.

A study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, as referenced in Fisher et al. (2017), found that the level of effort, or perceived exertion, is more critical for strength gains than the actual intensity of the exercise. This suggests that mentally pushing yourself, even during lighter weights, can drive significant gains, making RPE a valuable tool for bodybuilders.

Optimal Exertion for Muscle Growth

To maximize muscle growth, bodybuilders need to challenge their muscles with progressive overload—gradually increasing the weight, reps, or sets over time. Exertion must be balanced: enough to stimulate growth, but not so much that it leads to injury or overtraining.

Key strategies include:

- Proper Form: Ensure correct lifting techniques to maximize muscle engagement and minimize injury risk. For instance, maintaining a neutral spine during deadlifts ensures the effort is directed to the target muscles.

- Intensity and Volume: Balance the heaviness of weights and the number of sets and reps. For hypertrophy, rep ranges of 8-12 per set with rest periods of 60-90 seconds between sets are common, allowing for sufficient exertion and recovery.

- Rest and Recovery: Allow sufficient time for muscles to repair and grow after workouts. Muscle growth occurs during recovery, not during the workout itself, as the body repairs damaged fibers and synthesizes new proteins, a process supported by adequate rest and nutrition.

Different muscle groups may require different levels of exertion. Larger groups like legs can handle more intense exertion, while smaller groups like biceps might fatigue faster, requiring adjustments in volume and intensity.

As you get stronger, the same weight that once was challenging becomes less so, necessitating increased loads to maintain the same level of exertion, aligning with progressive overload principles.

Risks of Overexertion

Pushing yourself too hard can lead to several problems, particularly in bodybuilding where intense training is the norm:

- Injury: Overexertion can cause strains, sprains, or more serious conditions like rhabdomyolysis, where muscle tissue breaks down and releases proteins like creatine kinase and myoglobin, potentially damaging the kidneys. According to Cleveland Clinic, endurance athletes and those doing high-intensity workouts are at higher risk, especially if they push too hard without resting.

- Overtraining: Training harder than your body can recover from can result in decreased performance, persistent fatigue, increased resting heart rate, and mood changes. This can hinder progress and increase susceptibility to illness.

To prevent these issues:

- Warm up thoroughly before workouts to prepare muscles and reduce injury risk.

- Use proper lifting techniques, as improper form can exacerbate exertion-related injuries.

- Gradually increase your training load to allow the body to adapt, avoiding sudden spikes in intensity.

- Get adequate rest and sleep, as recovery is when muscles repair and grow.

- Listen to your body and take rest days when needed. Signs of overtraining include persistent fatigue, loss of strength, and mood changes, indicating it’s time to scale back.

Research from Clarkson et al. (2002) notes that exercise-induced muscle damage, often linked to overexertion, frequently occurs after unaccustomed exercise, particularly with eccentric contractions, emphasizing the need for gradual progression.

Practical Tips for Bodybuilders

To manage exertion effectively, consider the following:

- Measure Exertion: Use methods like counting reps and sets, tracking the weight lifted, using the RPE scale, monitoring heart rate, or keeping a training journal to record how you felt during each workout. This helps ensure you’re exerting yourself appropriately and making progress.

- Adjust Based on Muscle Groups: Larger muscle groups like legs can handle more intense exertion, while smaller groups like biceps might require lighter loads to avoid fatigue.

- Periodization: Vary the intensity and volume of training over time to avoid plateaus and prevent overtraining, aligning with training programs designed for hypertrophy as discussed in PMC Article on Bodybuilding Training.

- Nutrition and Hydration: Fuel your body with sufficient carbohydrates and proteins to support energy demands and recovery, and stay hydrated to aid metabolic processes.

Conclusion

Exertion is vital in bodybuilding, but it must be managed wisely. By understanding its physical, physiological, and perceptual aspects, you can optimize your workouts for muscle growth and strength gains while minimizing the risk of injury and overtraining. Remember, it’s not just about how hard you work, but how intelligently you work. Train hard, but train smart, and you’ll achieve the physique you desire